Before and after Columbus: disaster and reinvention

Reviews of 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus and 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created by Charles C. Mann

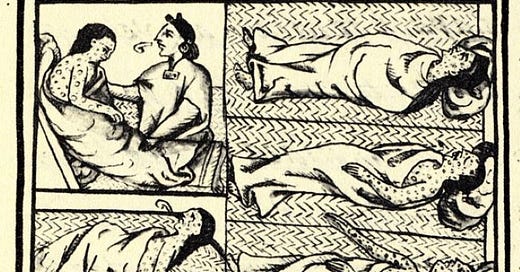

These books are predominantly based on archaeological and scientific evidence, a deep look at the way that Amerindians lived before and after the encounter with Europeans; the degree to which they controlled and shaped their environment; how the entire world changed when it entered the Homogenocene era, according to which man and not nature predominantl…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Crawdaddy’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.