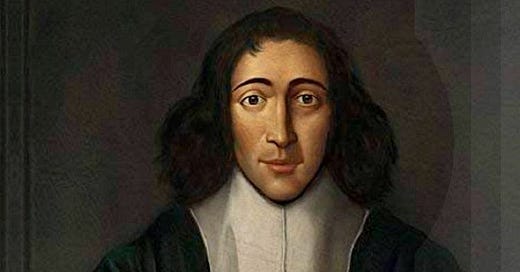

An early modern of great daring and courage

Review of A Book Forged in Hell: Spinoza's Scandalous Treatise and the Birth of the Secular Age by Steven Nadler

In this book, Nadler concentrates on Spinoza's Theological-Political Treatise as paving the way for secularism, even though he was not entirely “modern” by the standards of today. The ideas he entertained were "in the air" at the time. Spinoza not only to put them into a rigorous logical argument, but pushed them farther than others had dared. Eventually, his views got him ostracized and expelled from the Jewish community in Amsterdam.

First, Spinoza denied the divinity of the Bible, arguing instead that it was a book written by men to address problems specific to their time, hence limited in context and applicability. It should, he argued, be studied as a literary and historical document and most certainly was not the infallible word of God. He also questioned the motives of the learned men who wished to wield "the word" for their own purposes, interpreting the Bible in order to fit their own agendas. All of this was scandalously bold for its time, perhaps only possible in the tolerant culture of early Enlightenment Holland. However, it also took great courage, as an intimate friend of Spinoza was imprisoned for advocating similar views and died in custody.

Second, Spinoza identified God not as an anthropomorphic being that intervened "to set things right", but as nature itself, inseparable from necessity and immutable. Since God was all powerful in this formulation, everything occurred for a reason and was foreordained, there was nothing wrong that needed correction, however unfair the results may have appeared to those who suffered. Among other things, this meant that there were no miracles, no autonomous force of evil as embodied in the devil, etc. Not even prophets and their revelations were of exceptional or metaphysical value. Again, radical notions that threatened many, including denunciations from those Spinoza had assumed would support him.

Third, he argued, the value of religion was to be found in its popular presentation of a moral code, which could be arrived at just as well by reason alone, particularly by the educated. In his schema, the highest moral achievement was to live by reason rather than passion; to understand nature was to achieve harmony with God. (He had an extremely negative idea of organized religion, preferring a spiritual journey of the individual mind.) This was a precursor to both deism and the separation of church and state.

However, Nadler is very clear that Spinoza did not hold the views of the writer of, say, the American Declaration of Independence. According to Spinoza, the sovereign executive was responsible for the maintenance of peace and security. To do so, he was mandated to preside over religious matters, eliminating dissent when it threatened the status quo. There were also right and wrong answers that could be arrived at by reason, rather than differing points of view and interests that might be equally valid.

This is a wonderful and dense reading experience, opening onto the world of the early Enlightenment. I would have wanted a bit more context, in particular much more on how Spinoza differentiated himself from those with similar ideas.

Related reviews:

The Founding Fathers as epicurean atheists

All too often, philosophy books are the driest of academic reading experiences, advancing obscure proofs and arguments ridiculously disconnected from the real world and in completely awful prose. What Stewart accomplishes is to embed the philosophical convictions of the Founding Fathers into a riveting narrative of the formulation of the Declaration of …

From Humanism to the Reformation, as shaped by Erasmus and Luther

Why, I always wondered, were the Renaissance and the Reformation so rigidly separated in history courses and books? Not only were they near-contemporaneous movements, but their ideas – questioning the 1000-year assurances and traditions of the medieval ages – seemed eminently compatible, twin harbingers of the modern age. This book, a kind of double bi…

Elegantly argued claim that the Romantics opened a whole new avenue of philosophy

This is a splendidly dense introduction to the Romantic Movement. Berlin argues that the Romantics established a new kind of relativism and possibility, forever demolishing the 2000-year search for absolute certainty in philosophy. When the Romantics emerged, it was at the moment that reason had seemingly reached its apogee in the Enlightenment. With the…